|

|

|

|

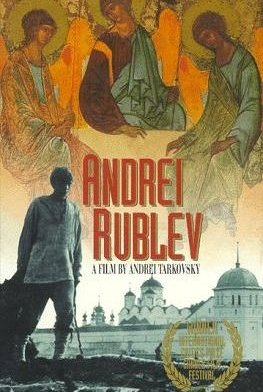

It is one of the great triumphs of mankind's stay on the planet, and a masterpiece almost without flaw. The beautiful painterly images follow one another in breathtaking succession. At least three of the eight chapters, if taken individually, could stand alone as separate masterpieces. Unfortunately, the film is not especially accessible to mainstream audiences, or even to casual scholars. One might liken Andrei Rublev to James Joyce's Finnegan's Wake as a work of genius so monumental and complex, and so disdainful of traditional narrative form, that it requires extensive thought and study to understand it. Even after studying it, watching it repeatedly, and reading Tarkovsky's own comments about it, one still finds it opaque in many ways. Tarkovsky's father was a poet, and the sensibility of poetry pervades the son's films. His films are to mainstream films as poems are to short stories. One does not read a poem for the clever plot or the accurate transmission of facts. Written poetry is about the feelings evoked by the use of words and rhythm together. Filmed poetry adds the power of images.

"A poem should not mean, but be."

- Archibald MacLeish -

The ostensible subject of the film is the life of Andrei Rublev, a 15th century monk who is renowned as Russia's greatest creator of religious icons and frescoes. The monk himself, however, is merely a useful device. Little is known about the historical Rublev, so most of the episodes in the movie come straight from Tarkovsky's imagination of what might have been. After all, sometimes one must ignore the facts to get to the truth. This isn't a movie about one talented and obscure monk, but about Russia. Rublev the individual is a useful symbol for his country, since he lived in a time when he could personally witness two of the key elements in the development of Russia's unique culture: the growing force of Byzantine Christianity, and the Mongol-Tatar invasions. In addition, he was an artist and a thinker, and thus experienced first hand the difficulty of following those paths in Russia. The artist's inner conflicts allow the filmmaker to illuminate thoughts on the pagan and the sacred, the nature of art, the relationship of the artist to the state, what it means to be Russian, and what it means to be human.

It is beautiful, mystical, and profound, but the truly inspiring aesthetics are matched with complete technical wizardry. I simply don't know how some of the shots were created, given the time and place where it was made. One I do understand, and stand in awe of, is a continuous single camera shot, just before a church door is breached by Tatar invaders, which involves action in several different locations at multiple elevations, as well as the correct timing of hundreds of extras and horses. It makes the first scene of Touch of Evil look like a high school film project.

Tarkovsky was free to create the work of art he wanted, without concern for profit. The original 205 minute cut was also free from outside censorship. He used this freedom to realize his personal artistic vision. There is no other movie like it, and there may never be.

And here's what you may have come for, the nude scenes. Clicking on the thumbnails will lead to much larger captures of the full frames.