| Let me cut to the chase. About 90% of

you will find this film to be insufficiently grounded, possibly even

totally incoherent.

But there is a sizable group of you out there who will like it. In fact, you will not only like it, but you may think is it the best movie you have ever seen. Here's a checklist of movies and movie types. If you like almost all of them, this will probably be your kind of movie:

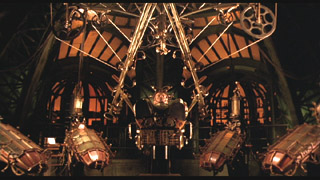

I like everything on that list, I saw similarities to each of them in this film, and I liked The City of Lost Children a lot. I didn't go ga-ga over it, but a lot of people do. It is not unusual for people to list this among their ten favorite movies. Let me tell you first why some of you will not like it. About a third of it takes place in a completely surrealist world - inside dreams and nightmares. The remaining 2/3 takes place in some kind of reality, but it is not our reality, and it will seem just as surreal as the dream world if you don't pay attention. I'm making this distinction because there is no way to determine the rules of the subconscious, which dominates the surreal landscape. In our dreams, there are no consistent rules. Sometimes when you fall from a great height, you soar like an eagle. At other times, you float like a hot air balloon. At other times, you fall to the ground below. There are no consistent rules. Part of this movie is, in fact, like that. The rest of the film's universe does have rules, but they are not our rules, and it is not immediately apparent what they are. The landscape of the world is, more or less, what the 20th century looked like in the minds of the people in the 19th. They had a vision of the future as being like their present, only more so. Theirs was a time of rapid mechanization, and emerging steam power, and their machines grew ever larger and more powerful. Although machines actually became ever smaller and quieter in the 20th century, the people standing upon the pinnacle of the Industrial Revolution thought that machines would have to get ever larger and noisier in order to do more. Like Jules Verne, they thought the the future technology would simply be a better, more powerful version of their existing technology - that rockets would be like big cannons, for example. Although we know now that steam power was eventually supplanted by more efficient energy sources, they lived in a world of steam engines, and steamships, and it was easy for them to imagine a future filled with steam cars and even steam planes. Although machines would become ever less machine-like by their standards, and would gradually evolve through electronics and transistors and plastics, becoming ever smaller and lighter and quieter, the people of La Belle Epoque would not have seen the future that way. They would have pictured a world in which work was performed by the turning of enormous grinding gears on gargantuan machines covered with the tens of thousands of rivets necessary to hold the machinery together in face of the wear and tear caused by the turning of those massive moving parts. That is the world of the City of Lost Children, the Industrial Revolution gone mad with ugly, snorting, belching metallic machines which have made the sun disappear forever, and have made "rust" the dominant color of the earth. A world we probably narrowly avoided ourselves. In this ugly reality, on a mechanical island which resembles an oil rig, there lives a man named Krank. He is a very bad man, although perhaps his life might have been different if he could dream. Because he cannot dream, his aging process is accelerated, and his mind is forced to the brink of madness. He is as much tragic as loathsome. He is some kind of genius as an inventor, however, and his latest advancements consist of dream-stealing machines, for if he cannot dream his own dreams, he must steal the dreams of others, tuning into their brains, watching their thoughts. For some reason not completely clear to me, but probably explained somewhere, his precise need is to steal the dreams of very young children. To facilitate this process, he has assembled a team of ugly, deformed, lowlife sleazebags who kidnap children for him. His criminal band is not the usual gang of thugs. One member is a brain housed in a fish tank mounted on a giant record-player console, complete with stereo speakers. (By the way, the Teenage Mutant Turtles were opposed by a nearly identical villain, whose name was Krang!). Six members of the mob are his "sons" - identical clones. The clones and another character are played by the unusual looking Dominique Pinon, who looks like Chris Kattan doing an impersonation of Robin Williams making funny faces. There are many other baddies who look like the Cyclops, and some who look like the Oompa-Loompas. One day Krank's gang makes a terrible mistake. They steal Little Brother, adoptive brother of the strongest man in the world, a simple-minded circus strongman named One (Ron Perlman, of TV's Beauty and the Beast). The child-man named One comes after his brother, and eventually finds an accomplice to assist him in the project, somebody to provide the guile and cunning necessary to complement his own strength. His partner is Miette, a child-woman of another kind, one of the Lost Children. They are a group of kids, far wiser than their years, who move stealthily through the shadows of the seacoast town near Krank's lair. The film is about the quest of One and Miette to free Little Brother and the other kidnapped children from the clutches of the evil Krank. (You get a gold star for movie knowledge if you noticed a strong parallel to the two main characters in Luc Besson's "Leon - the Professional", the strong man with the mind of a child, and the female child with the mind of an adult.) |

|