Hollywoodland (2006) from Johnny Web (Uncle Scoopy; Greg Wroblewski) |

|

"Hollywoodland" is what the "Hollywood" sign said

in 1923-1949, in the heyday of the film industry. The sign was originally created to advertise

a housing development up in the hills, but as the film industry

burgeoned, the sign gradually took on a larger, symbolic meaning as

a metaphor for everything Hollywood represented to America. It

might well have had a sub-heading like "welcome to the dream factory."

The sign's symbolism gained a deeper meaning in 1932 when starlet Peg

Entwhistle committed suicide by leaping from the letter "H." In

essence, Entwhistle expanded the sign's symbolic connotations to include the

failure implicit in the hope for success. For every would-be star

who came to California and made it big, there were dozens or hundreds

doomed to obscurity or outright failure. In 1949, the Chamber of Commerce of Hollywood offered to pay for the refurbishment of the dilapidated sign in return for the right to remove the last four letters, thus making it a world-recognized tourist attraction and a beacon for their community. The truncation of the sign meant that the old phrase, "Hollywoodland," would forever be the telegraphic way of saying "the way the movie business used to be in the old studio days, with big dreams both realized and broken." |

|

|

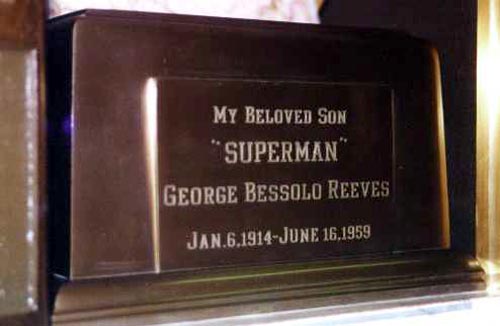

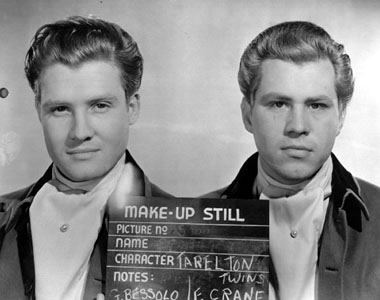

The actor George Reeves (real name George Bessolo)

could also be cited as a

symbol of the very same period. He came to the movie business as a

strapping, handsome hunk with stars in his eyes, and his very first

credited role was in the opening scene of the most famous movie ever

made, Gone With The Wind, as one of the Tarelton Twins. (Left, looking

like Liberace.)

He seemed to be on his way to his personal dream - a career as the next casual, good-natured, unpretentious leading man with a gift for the one-liners. The new Clark Gable. He had some hits and some misses in the forties, but every time his career seemed about ready to accelerate, something would happen to stall him out. Of course, there were a lot of guys who wanted to be the next Gable, and they couldn't all be stars. And there was a war on, after all. So George took the roles he could get while he socialized, charmed, partied, and schmoozed every time he got the chance. Before he knew it, thirteen years had passed and it seemed that he would never achieve fame or financial security. A 25-year-old guy who dreams of stardom is something that makes people smile in empathy. A 38-year-old man in the same boat is just kinda sad. |

|

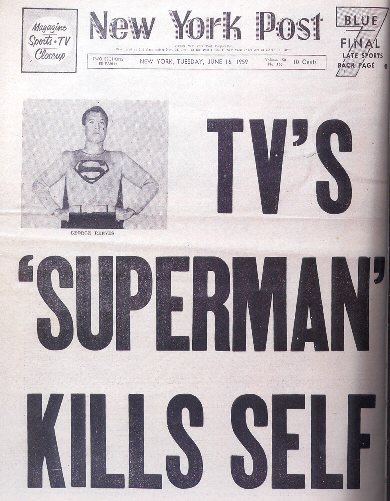

Then Reeves caught a break. Not the break he dreamt of, but perhaps the best break he could possibly hope for in his situation. He landed the lead role in one of the most popular shows of early television, The Adventures of Superman. 104 shows later, he was probably more famous even than Gable, but with the ironic twist that he had no career to look forward to. While the TV series had made him universally recognized, it had also left him hopelessly typecast. The powers-that-be felt he was so completely associated with the character of Superman that audiences would never accept him in any other role. By 1959, Reeves came to realize that the rest of his life would consist of strangers pointing and saying, "Hey, there's Superman," whether he was on the screen or in the streets. He knew by then that his acting career was coming to a close. He could only play Superman, but being 45 years old and a heavy drinker, he could not play Superman much longer. Not only did Superman take away his acting future, but it failed to give him financial security as compensation for his loss. He was paid about $2500 per episode to do the show, a number which put him in a higher tax bracket than our moms and dads, but left him far short of big-time Hollywood wealth. He thought there was a way out. He had a reputation as a good-natured, bright, funny, and genuinely nice person, and he hoped to cash in on all the friends he had made and the favors he had done by moving behind the camera into production or direction. (He had directed some episodes of Superman.) This might have worked except for one very messy situation which created a powerful enemy. For years Reeves had been the toy-boy of the much older Toni Mannix, whose husband was the general manager of MGM. Eddie Mannix knew of his wife's affair and approved tacitly, so the Mannix relationship itself did nothing to hurt Reeves's career, but ending the relationship was another story. Reeves broke off with Toni Mannix to take up with a younger "society dame" named Lenore Lemmon. Toni could not accept the break-up and continued to harrass Reeves telephonically, to the point where Reeves actually sought legal relief. More important to the Reeves life story, Eddie Mannix was very upset that his wife was so upset. The situation made Eddie an enemy of George Reeves, and Eddie, one of the toughest and one of the most powerful men in Hollywood, was the wrong man to have as an enemy if one hoped for a career as a producer or director. That is the background for Hollywoodland the movie, which looks back on the life of George Reeves from a starting point of June 16, 1959, when Reeves died in his own home in the wee morning hours. Cause of death: a gunshot to the temple. |

|

|

In real life Reeves's mother, Helen Bessolo, rejected the official coroner's verdict of suicide and hired Jerry Geisler, detective to the stars, to investigate. In the film the high-powered Geisler has been replaced by a low-rent film noir style detective named Louis Simo, who acts as our eyes and ears in the investigation. Both detectives, real and fictional, turned up enough evidence to cast some doubt on the suicide verdict. The police were not called until 30-45 minutes after the incident. There were no powder burns on Reeves's temple, and his hands were never examined for powder burns. There were no fingerprints on the gun, although Reeves's hands were ungloved. The bullet seems to have been shot from below his head, moving upward and lodging in the ceiling. The gun and the spent shell were found in places inconsistent with a self-inflicted wound. Reeves left no suicide note. Everybody seemed to report that his recent spirits were quite optimistic - he was to be married in three days, he was planning a glamorous honeymoon, and Superman had just been renewed for some new episodes with a big pay raise for Reeves. In addition, Reeves never put his affairs in order. His will was outdated, and left all of his possessions to Toni Mannix, his estranged lover - a fact which indicated that he felt there would be plenty of time to change it. The film posits three possibilities to explain the Reeves death: (1) it was a suicide (2) Lenore Lemmon shot Reeves in an argument (3) mob-connected Eddie Mannix had Reeves killed. The script does not really lean strongly toward one of the three. The detective imagines each of them in turn, without taking a position, as if to tell us that the key point is not how Reeves died, but what we learn from the fact that all three might be possible, things like:

|

|

Those facts either tell us a lot about Hollywood, or a lot about our own gullibility. Maybe both. I'll tell you what they tell me. The fact that the film narrows down the possibilities solely to those three tells us a great deal about how we need to have mysteries and conspiracies instead of simple, undramatic solutions. Damn Occam and his razor. There is a far more logical explanation than any of those three. Reeves killed himself accidentally. The autopsy revealed that his blood alcohol level was .27. (.35 is considered fatal.) Imagine the point where you were the drunkest you have ever been. Now imagine that you had five more drinks after that point. That's how drunk Reeves was. As if that weren't enough to impair his judgment, he had also been taking pain killers. So he was totally pickled, he had no reasonable level of control over his bodily functions, and he was in a bedroom with a loaded gun, which he may or may not have realized was loaded. Is it unreasonable to imagine what really happened? I don't think so. And the people at that party with him? Maybe they didn't call the police right away because they were playing loud music and didn't hear the shot. Maybe they were just a bunch of loud, sloppy drunks arguing about what to do. Maybe they had something illegal in the house (marijuana? another gun? prescription drugs?) that they had to ditch before the cops showed up. Maybe one or more of them argued that he needed a cover story because he told somebody he was elsewhere. That's the way life goes, especially when everyone is blitzed out of his mind. Here are some other comments made by people more expert than I in these matters:

In other words, there is really nothing in the evidence to contradict the theory that Reeves shot himself accidentally. That is probably the most logical conclusion, yet the film never even considers it. After all, it's not very dramatic, and doesn't offer any new ways to look at ourselves. Guy got shit-faced and screwed up big-time. Or maybe the guy had some suicidal tendencies, and his degree of drunkenness removed some of his inhibitions. Or maybe he was merely contemplating suicide while drunk, and .... well, you can guess the rest. Who knows whether he ever really meant to pull that trigger? He probably wasn't sure himself. Maybe it was completely accidental, maybe intentional, maybe semi-accidental, but still death at his own hands. End of story. No lesson learned. As to the movie's execution, well, I thought it was a pretty good flick, but it was not what I hoped for. I hoped for something jazzy, jaunty, and cool like L.A. Confidential. There was too little of that, and too much about the sleazy, depressing life of the low-rent detective played by Adrian Brody. The film runs 126 minutes. I would either have pared it down by eliminating the detective's character development, or kept it the same length while devoting the dick's time to more scenes involving the affable George Reeves and the peculiar charm of early television. For one thing, virtually every scene with Ben Affleck as George Reeves is engaging, but even more important than that is the fact that we're buying a ticket to see the story of the real-life star, not the imaginary detective. I am interested in George Reeves. I am not interested in the fictional Louis Simo, or his sleazy practice, or his girlfriend, or his family. The Simo investigation scenes seem to convey the message that almost everybody is corrupt and even when they are not, they always get everything wrong, even with the best of intentions. The Simo investigations turn the film away from the entertaining noir it might have been and make it more of a somber arthouse film. Adrian Brody is a creative performer who had an interesting take on the material, but his character of Mr. Simo should have been a device, nothing more. End of story. If the Simo investigation scenes are depressing, the Simo family scenes are basically complete bullshit. Simo's son goes through all kinds of trauma about the death of Superman, and the script implies that this was some kind of national epidemic. Oh, give me a break. I was ten when Reeves died. My friends and I were saddened to hear of it, and curious about it, but we all knew the difference between an actor and the role he played, and we knew that there were troubled people in the world, and so did our younger brothers and sisters. Kids are frightened of the world, but not stupid. As I recall, we even made jokes about it. ("How come it didn't bounce off him? Was it a Kryptonite bullet? Hey, wait, I thought he was faster than a speeding bullet. Why didn't he just duck?") We took much more note when Buddy Holly and Richie Valens died, earlier the same year. We took much more note when budding star Harry Agganis of the Red Sox died at 26 of sudden and natural causes, because that seemed to imply death could come to anyone at any time, even if they were young, healthy, and untroubled - to our dads, for example, or even to ourselves. But George Reeves? Meh. He was an actor. Seemed like a really cool guy, but still an actor. Not Superman. So are there good things about the film? Yes, absolutely. First of all, you have to love any script in which Diane Lane says, "What does she do, blow smoke rings with her cunt?" More important, as mentioned, the George Reeves scenes are just fine - atmospheric, energetic, and entertaining. These scenes can be very funny, touching, and sometimes just plain great - as when a costumed Affleck-as-Reeves-as-Superman has to talk down a child who seems to want to fire a real gun at him to test his invulnerability. Ben Affleck is completely convincing and remarkably appealing in the role. He also seems to be channeling the old-fashioned good looks and calculated charm of the real Reeves, especially in the Clark Kent scenes, when you have to look carefully to distinguish the original footage from the re-creations. And that's a great thing, because the real Reeves was charismatic, fun to watch, and fun to be around. Affleck could reasonably be considered an Oscar candidate for his work. Based on that, I would have given the film top marks across-the-board if Simo's role had been minimized and if the film had given at least some consideration to the obvious possibility of a drunken accident. Even as it stands, although it does not have a Best Picture Oscar or a blockbuster gross in its future, it is certainly worth a look for anyone interested in 1950s Hollywood and the former Tarelton twin who was swallowed up by it. |

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

||||