|

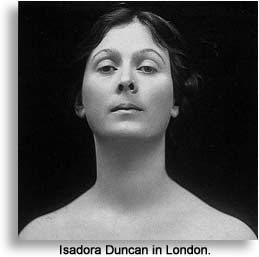

"I have discovered the dance. I have discovered the art which has been lost for two thousand years." ... Isadora Duncan, whose "discovery" featured plenty of flowing garments and scarves. "Affectations can be dangerous."

... Gertrude Stein's acerbic comment about

Isadora Duncan's having been killed by her

ubiquitous flowing scarves. This film is a biopic of one of the eccentric free spirits of the early 20th century, the American dancer Isadora Duncan. Many people consider Duncan to have had the same relationship to modern dance that Picasso had to modern painting in that she rejected the stuffy, highly conventional constraints of classical ballet and defined expressive 20th century dance in her own image. Duncan not only flouted traditional concepts in dance, but in morality as well. She had physical relationships with women as well as men. One of her male lovers was the theater designer, Gordon Craig. Another was Paris Singer (heir to the sewing machine fortune), who gave her lavish gifts, including her own dancing school. She married neither, but bore a child by each. Both children were tragically drowned in an accident on the Seine River in 1913. Although Isadora had sworn never to marry, she finally broke down in 1922 and wed a handsome, permanently drunk, certifiably insane Russian poet named Sergei Yesenin, who was 17 years younger than she, and was known to be a serial seducer. Although he barely lived past his 30th birthday, Yesenin managed to marry at least five women in his short life, and to father children by at least one more. He and Duncan must have had some incredible physical passion because they had no common language. According to her biographers, she knew no more than a dozen words of Russian, and he spoke no English at all. You well may wonder how Isadora and Yesenin could have gotten together in the first place. They were linked by both art and politics. Inspired by the idealism of the workers' revolt, Isadora spent a considerable time in Russia just after the revolution. That country embraced her as a fellow revolutionary and gave her an old palace to use as a dancing school. The 26-year-old Yesenin was then considered one of Russia's greatest artists despite his youth, and was a spectacularly handsome hunk. The two sexually-charged artistic spirits met, and nature took its course. Yesenin would accompany Isadora on an American tour in 1922-23, but his alcoholism fueled frequent destructive rages, similar to the hotel room rampages of today's rock stars, and those incidents caused much negative publicity for both of them, but probably not as much as their politics. The occasional trashed hotel room was probably more acceptable in the United States than their fanatical Marxism. During a performance in puritanical, capitalist Boston, she managed to combine "immorality" and Communism in a single stage performance, by baring her breast while waving a red scarf and proclaiming, "This is red! So am I!" Yesenin soon left Duncan, returning to Moscow and managing to marry a few more women in the short time before he would be institutionalized for mental illness. It was not long before he would commit suicide. Duncan's own life ended no less tragically than those of her children or her crazy poet. She always wore scarves which trailed behind her, and this affectation caused her death in a freak accident. She was killed when her scarf caught in the wheel of her friend's Bugatti automobile. As the car sped off, the long cloth wrapped around the vehicle's axle. Ms. Duncan was yanked violently from the car and dragged for several yards before the driver realized what had happened. She died almost instantly from a broken neck. Although the fatal accident occurred in Nice and Duncan had been living in France for some time, she died a citizen of the Soviet Union. The unconventional socialist actress Vanessa Redgrave, eventually a six-time Oscar nominee, was a perfect choice to evoke the unconventional socialist dancer, and she was rewarded for her memorable performance with Oscar and Golden Globe nominations, as well as the Best Actress award at Cannes. The film itself is far less impressive than Vanessa's performance. It follows a shopworn structure, using a framing device in which an aging Isadora dictates her autobiography, "Ma Vie," to her amanuensis, with each recollection leading to a flashback to a key incident in her life. That framework cobbled the narrative into all the usual biopic mistakes. The story is too long and rambling and pointless, and tries to pack Duncan's entire life into its running time instead of focusing on an important thread or a memorable portion of that life. We sit back and watch Isadora trot around the globe, apparently abandoning in succession each of the projects she had been so passionately extolling the virtues of in the previous scene. The film could have compensated for its unfocused script with some great musical numbers, but the dancing scenes are mostly repetitive. If you watch this film without knowing anything about Duncan's contribution to dance (which places you in the boat with me), you will conclude that Duncan's entire schtick consisted of wearing flowing gowns, trailing a diaphanous scarf, bending her knees, pointing her toes, waving her arms, and acting "free" while prancing about like a twelve year old who dreams of being a dancer. I suppose Duncan must have done some of that on stage, but surely it could not have been her entire bag of tricks. I would not have complained if she had done this once, but the process of prancing aimlessly around a room must occupy close to an hour of the film's running time, and it looks exactly the same every time. In fact, I was about ready to shout, "Will you stop prancing around the goddamned room?" at the screen, when one of her lovers uttered those exact words! I did, however, enjoy Vanessa's prancing much more on the one occasion when she did it naked. |

|

|

Although the film doesn't cohere very well, there are some great individual scenes. I liked some of the Russian material quite a bit. The one dance scene that is significantly different from the others is Duncan's first performance in Russia. The lights go out while she is performing, and the night seems doomed to be a failure, but everyone there improvises, including the audience, and the participants end up having the most memorable night of their lives. Someone in the Russian audience provides a lantern, then the audience members gradually start to sing to provide musical accompaniment. One man manages to produce a squeezebox. (Russians always carry one, don't you know? Astoundingly, in a presumed violation of the Soviet constitution, or at least in violation of the prime directive of Russian screen clichés, nobody there had a balalaika!) Several men join Duncan on stage for traditional Russian dancing. The film managed to capture the whirlwind of that moment. That scene got me. I was clapping along, completely drawn in. Unfortunately, it takes the film nearly two hours to get to that point. That wait could be excruciatingly boring at times, and I got the impression that Ms Duncan was both pretentious and mentally ill. If the rest of the film had been as invigorating as the Russian part, I might have enjoyed spending all those minutes with the eccentric characters and their repetitive behaviors, but it wasn't and I didn't. |

|