|

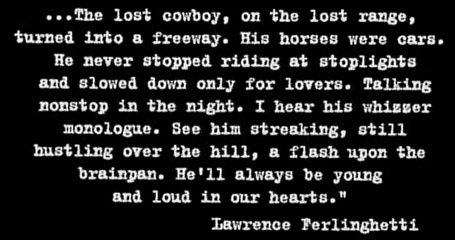

This is the second time that a film has tried to capture the man described above, the mercurial Neal Cassady, king of the beats. The beats were the writers who provided the spoken and written voices for the first generation of the post-war counter culture in the States. While mainstream America, after a decade and a half of Depression and war, was happy to embrace the superficial pleasures of the new consumer culture engendered by post-war prosperity, a group of intellectuals and contrarians believed that there was more to life than having babies, buying new cars, and settling in the suburbs. The actual term "beat" was coined by writer Jack Kerouac in 1948 when he told his friend Clellon Holmes: "You might say we're a beat generation." Four years later, Holmes made it all official in an article for the New York Times Magazine, entitled "This is The Beat Generation." The original membership roster of the Beat Generation basically consisted of two Columbia students, Jack Kerouac and Alan Ginsberg, and a few others they met along the way, most notably author William Burroughs. Ginsberg and Kerouac were both profoundly influenced by a young man from Denver named Neal Cassady, who met the famous beats when he visited friends at Columbia. Cassady was a handsome, hyperactive, smooth-talkin', fun-lovin', con artist who worked in blue collar jobs at night and read Proust by day. He embodied the anti-conformist mentality. He dressed casually. He experimented with drugs and enjoyed debauched sex of all types with people of all races and both genders. He earned only as much money as was necessary for sustenance. He was the coolest of the cool, the hippest of the hip. His major talents were sex and story-telling, and he was more adept at living life than writing about it, so Cassady never became a great writer himself, but he was the muse for many, and appeared as a character in the work of several prominent counter-cultural works of the beat and post-beat eras. Cassady was so admired by the beats that he almost single-handedly managed to cause their migration from New York to San Francisco. When Cassady moved to California from Denver, Ginsberg, who was in love with the omnisexual Cassady, soon followed, with Kerouac not far behind. There the Columbia lads met up with the Berkley poets whose literary movement centered around the City Lights Bookstore and City Lights Press run by Lawrence Ferlinghetti. The merging of the two groups spawned a bohemian literary culture which they envisioned as the hipster equivalent of Paris in the 30s. Their writing rejected the standard narrative format, and they liked to say that it employed the same rhythms and improvisational riffs as their jazz heroes, Charlie Parker, Miles Davis, and Thelonious Monk. The early beat movement may have been little more than an outré lifestyle which included some self-congratulatory poetry readings, but it made the quantum leap toward being a recognized literary movement in 1956-57 when some of the group achieved national prominence. Their fame began with a City Lights edition of a long Ginsberg poem called "Howl", which received some national attention because its publication and sale landed Ferlinghetti in court, facing obscenity charges. The beats truly entered the mainstream of American consciousness following the publication of Kerouac's "On the Road," which somehow crossed over into popular culture and become a national best-seller. Since Neal Cassady was the model for Dean Moriarty, the most prominent character in that best seller, he became an underground hero, the recognized icon for everything beat. If the 50s had been more like the later years, Cassady's handsome face would have been on every poster and every t-shirt on every college campus in America. As it was, he had to settle for the oxymoronic "anonymous fame" of being unknown to the world as Neal Cassady, but universally famous as Dean Moriarty. As much as the beats idolized him, Cassady was never as much of an outsider as they. Although he joined his beat buddies for the occasional debauch or road trip, and though he sympathized with their ideals, he always kept one foot firmly planted in Middle America, where he maintained normal marriages, wore normal haircuts, worked mundane jobs, and raised three children. The conflict between the two sides of Neal Cassady is essentially what The Last Time I Committed Suicide is about. It is based on a long letter Cassady wrote to Kerouac in the early 50s in which Cassady's distinctive hipster lingo described how he felt about being torn between a desire for a suburban home with a white picket fence on the one hand, and the free life of a rebel drifter on the other. The storyline is minimal. Cassady meets his true love. She tries to commit suicide after having sex with him. He visits her a few times in the hospital, but stops coming because she seems to have lost her will to live. Somehow, she survives and finds him. On their first night back together, before they make love, Cassady decides to wander out to get a suit he needs for a job interview which is to take place the next morning. He promises to return, and his intentions are good, but he can't resist the temptations of pool halls and beer joints and underage girls, and he soon finds himself in jail, having permanently screwed up his relationship with his beloved. This film works, but it's not because of the plot. It works because of some excellent characterization from Tom Jane (who is exactly what I imagined Cassady to be like), some great minor characters, Cassady's wild anecdotes and vivid descriptions, and because of a crazy kind of experimental moviemaking style which seems to capture the essence of the beat attitude. It isn't the most cohesive narrative or the deepest thinking you'll ever see, but then again it isn't supposed to be. All it is supposed to do is bring to life Cassady's letter to Kerouac, so that we can see what happened through his eyes and in his words. To that extent, I found it very successful. I was transported into those few days in Cassady's life, and never emerged from my trance until the story had ended and Cassady had made the case for why he needed to keep one foot in each of his contradictory worlds. It's not a big mass-audience movie. It's the film equivalent of a beat poem, which was in turn the literary equivalent of a jazz riff. Many viewers will find it too self-consciously stylized and arty, as many people once found the whole beat movement in general, but if you are interested in Cassady, this seems to capture his spirit very well, and the film has a tremendous be-bop score from Charlie Parker, Thelonious Monk, and others. |