There are two types of writers. The first type consists of great

story-tellers who glue our eyes to their works. We just can't

put their books down because we need to know what happened to the

characters. The second type consists of those who exert mastery over

language. They use it playfully when they want to amuse; they use it

powerfully when they want to move or inspire; sometimes they just use

it because they love the way it resonates. Most of the truly great

writers come from type two, like Shakespeare, Gabriel Garcia Marquez,

and Nabokov, but most of the truly great cinematic book adaptations

come from type one - writers like Stephen King, Mario Puzo, Harper Lee,

Raymond Chandler, and Ken Kesey.

That is not to say that these are universal laws. There are great

writers who were primarily story-tellers, like Cervantes and Tolstoy;

and there are great movies made from language-rich source works, like

A Clockwork Orange. As a general guideline, however, the works of

great type two writers are difficult to adapt into worthwhile films.

It may be a sad fact of our existence, but it is nonetheless true that

one is more likely to create a great film from a Chuck Palahniuk novel

than from a William Faulkner masterpiece.

It's good for potential screenwriters and directors to consider the

following axiomatic. If a great writer is great primarily because of

the way he masters language, one may make two assumptions: (1) it is

nearly impossible to translate that particular type of greatness into

cinematic terms; (2) it is completely impossible to do so in another

language. A literal-minded translation of Hamlet in Polish is just a

crazy-ass story about some fruitcake from an obviously inbred

royal family who builds up a Rambo-sized body count based on his

conversations with a ghost.

Well, a Polish version of Hamlet makes no less sense than an

English-language movie based on a masterwork of Gabriel Garcia Marquez.

The written version of Love

in the Time of Cholera is a great work because of the magical spell

Marquez weaves with language - another language - and the devices he

uses to create that enchantment, like diaries and love-letters which

are essentially his alternative forms of interior monologues.

The New York Times selected no less an author than Thomas Pynchon

to review the novel Love in the Time of Cholera, and he could scarcely

have been more enthusiastic about what he called a "shining and

heartbreaking novel":

"And - oh boy - does he write well. He writes with impassioned control,

out of a maniacal serenity: the Garcimarquesian voice we have come to

recognize from the other fiction has matured, found and developed new

resources, been brought to a level where it can at once be classical and

familiar, opalescent and pure, able to praise and curse, laugh and cry,

fabulate and sing and when called upon, take off and soar, as in this

description of a turn-of-the-century balloon trip:

''From the sky they could see, just as God saw them, the ruins of the

very old and heroic city of Cartagena de Indias, the most beautiful in the

world, abandoned by its inhabitants because of the sieges of the English

and the atrocities of the buccaneers. They saw the walls, still intact,

the brambles in the streets, the fortifications devoured by heartsease,

the marble palaces and the golden altars and the viceroys rotting with

plague inside their armor.

They flew over the lake dwellings of the Trojas in Cataca, painted in

lunatic colors, with pens holding iguanas raised for food and balsam

apples and crepe myrtle hanging in the lacustrian gardens. Excited by

everyone's shouting, hundreds of naked children plunged into the water,

jumping out of windows, jumping from the roofs of the houses and from the

canoes that they handled with astonishing skill, and diving like shad to

recover the bundles of clothing, the bottles of cough syrup, the

beneficent food that the beautiful lady with the feathered hat threw to

them from the basket of the balloon.'''

Those passages are eloquent even in translation. But the actual

events portrayed by the work are no different, more or less, than a

summary of a year of General Hospital. The portion of the plot which

has survived into the film is a simple one. An old man dies. Another

old man realizes that the death represents his last chance at the

widow, who happens to be his true love. He professes his love on the

day of her husband's funeral, and the widow finds that highly

inappropriate, so he is sent away with his memories ... (cue

flashbacks). After some two hours of flashbacks to show us the

origin and progression of the romantic triangle, the story returns to

the two old coots. Will they reconcile to swelling music, or will they

remain separated forever? I'll bet you can guess.

There's the film's problem in a nutshell. Without all the book's

eloquence, without that brilliant, evocative and often playful use of words,

what's left for a movie? Just the soap opera plot about a love-sick

Colombian in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

And the performances are not good at all. The actors - even the

ones who do not normally speak English with any sort of Spanish

intonation - speak with cartoon accents that would embarrass Bill

Dana and Senor Wences. The actor John Leguizamo was born in Colombia

and can speak Spanish when needed, but normally speaks English with no

accent other than a tinge of New Yawk. Here he speaks English with

some kind of wacky accent which barely sounds Spanish. He sounds more

like Long John Silver. As for Liev Schrieber, the man is a great

actor, but I expected him to sell me a Chrysler Cordoba with rich

Corinthian leather.

On the other hand, the clumsy convention of having the Spanish

language represented by English with comical accents is merely one small drop in

the vast ocean of bad acting on display in this film. Many of the

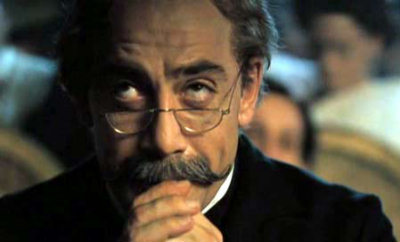

performers are grossly miscast. The normally commanding Javier Bardem gives

an awkward impersonation of a love-sick youth turned love-sick coot,

as he shambles with baby steps, his head lowered and his shoulders

turned inward in a performance more appropriate for a high school

play. He does, however, turn in a great impersonation of Groucho:

Bardem seems like a master of subtlety compared to poor John

Leguizamo. John can be excellent in both comedies and modern urban

dramas, but he's a fish out of water in this period piece. Turning in

a performance from the Snidely Whiplash school of acting, Leguizamo blusters, sneers and

snarls, twirls his moustache, raises his eyebrows separately, and

gesticulates wildly, failing to embody the perfect heartless conniver

only because of his inexplicable failure to send any bound damsels

into a sawmill.

And neither of them was the worst performer in the film. That would

be Angie Cepeda, who was so bad that I'm shocked her scenes were not

re-shot. You know your historical romance is in trouble when your best

period actor is

Benjamin Bratt.

If the performances weren't absurd enough to begin with, they are

raised to the level of Benny Hill silliness by the ineffective old-age make-up,

which the director keeps insisting on capturing in close-up after

unrealistic close-up.

I don't want to argue that the movie is awful, although some

aspects of it certainly are, but I feel I should prepare you for what

it really is: not a cinematic interpretation of a great work of art,

but simply a mushy soap opera photographed magnificently on location

in Cartagena in rich golden hues, backed by lush orchestral

arrangements and some soulful native folk songs. (Señor

García Márquez himself convinced the famous Colombian singer Shakira

to provide three songs for the film.) In addition to the heavenly

scenery and music, the women are universally divine, and they are frequently

topless in entertaining scenes, so the film is not without its charms.

I kind of enjoyed the film for what it was, and I would have enjoyed

it even more if it had run somewhat shorter than its existing 129

minutes, but it's a shame

that those few elements are the only worthwhile remnants which could

be salvaged from an acclaimed work by a

Nobel laureate.