|

Madhouse came pretty close to being an excellent horror film, but it didn't get there, and it may be useful to discuss why. The entire film begins with various disconnected visions of random madness, which flash before us like a horrible nightmare in the opening credits. This is not the kind of material that should begin a movie, because it has no context. We don't know the purpose of the stream of consciousness, and we don't know the characters or situations we encounter. Consequently, we can't be drawn in, and equally important for a horror film, we can't be scared. I'm not sure how all of you will react, but my reactions proceeded like this (1) irritation - what is the frickin' point (2) more irritation - when is the frickin' film going to start? (3) sheer boredom. Completely uninterested in what was going on and having no idea what it meant, my mind wandered off to other things (4) snapping back with the realization that I need to walk out if something sensible doesn't begin soon I suppose that's Lesson One: making sure your cinema appliance is properly grounded. No scenes of madness until you earn them, Mr. Director. We viewers need to know whose madness we are watching, or why, or what the images are, or even all three. Run the exact same sequence later, and it might draw me in, even give me some chills, and will at least get me curious enough to watch it. You don't have to provide all the answers, but you do have to provide all the questions. That brings us to Lesson Two: The Stephen King Rule. If you want to shock or frighten me with what is happening to the characters, you have to first get me to identify with the characters and/or their situations. This is one of the reasons why Stephen King's work is so effective. He starts out by establishing that the characters are normal people leading normal lives with their kids and pets. The situation has to be credible, and I have to care whether your characters get threatened. Never happened here. Once this film's loony opening credits are finally done, it begins in earnest with a new intern reporting to a mental institution. He walks in the front door to a lobby. Nobody there. There is a reception area. Nobody there. No problem. Right in plain sight, within reach of the visitor, is the button which releases the security door. You think that is convenient? We haven't even begun to scratch the surface of how convenient this madhouse is. The buzzer is not only in reach, but it is conveniently labeled "security door" because, you know, the receptionists forget when they have so many buttons to worry about.

Now that's convenient! If it were any more convenient, they'd have to install a Slurpee machine. In some ways, it's even better than 7-Eleven because they let you in without a shirt or shoes. Best of all, when you do walk in, you can meet the patients immediately. There are no inconvenient doctors, nurses, or orderlies to interfere with your observations, and the nutburgers are just barely inside the security door, acting conveniently nutty at all times, some pacing around aimlessly in their jammies reciting Hamlet's speech to Yorick's skull, others wearing the Napoleon hat, and still others dressed up in medical scrubs, pretending to be the doctors. When the intern finally gets in to see the head shrink, the beardless youngster starts off the meeting with the wizened old expert by presenting a paper he has written recommending changes to the institution. Yeah, that'll get him off on the right foot. I guess that would be pretty damned ballsy for anyone, so I'm thinkin', "this can't really be happening." Then something else dawns on me, and two questions pop into my mind - (Question #1) How can he be making recommendations for change when he hasn't even been shown around yet? (Question #2) Why doesn't the hospital administrator also ask question #1. |

|

|

Then I look around the doctor's office. It is filled

with crazy-lookin' clocks including a cuckoo clock (great sense of

humor for the head of a mental institution, eh?). Each of the clocks

shows a different time.

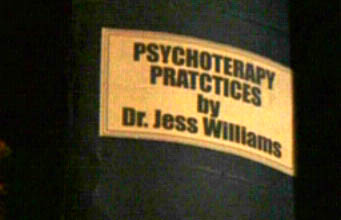

Then the camera pans across the shelves. Wise medical tomes on the wall have misspelled titles. (Pictured to the right). I guess I could understand misspelling "psychotherapy." That's a hard word, although it might not be so hard for psychotherapists. But "practices"? That's a pretty simple one. And in a book with a two word title, you'd think the publisher could at least get one of the two right. |

|

|

As soon as I saw all of this nonsense, immediately following the crazy, disconnected opening credit montage, I'm thinkin' "OK, the whole thing takes place in this visitor's mind. It's some kind of surrealist mindscape, right?" Nope. That was supposed to be a regular day. Business as usual in the nuthouse. That was the problem. I was supposed to be buying into that as reality, but I never thought that for a second. From the moment the intern let himself into the madhouse with the self-service security buzzer, I thought it was some alternate reality created by his own insane mind. Thus I could never experience the story as I was meant to. Back to the Stephen King rule again - ya gotta take time to hook the fish before you can reel him in. Or to put it another way, if ya wanna fuck with me, ya gotta kiss me first, and get me ready. Setting those inept metaphors aside for a moment, the film has some interesting elements. The director does exhibit some talent for scary moments. The story combines a murder mystery with a supernatural overlay and a horror/slasher ambiance, and it all takes place within an underbudgeted, understaffed madhouse, so the film has some creepy, demented ambiance to it, Sadly, those elements just never coalesce because the film doesn't take the time to establish credible reality and let us identify with the characters before it starts going all surreal and batshit crazy. Sidebars:

|

|